The dominant influence on Ireland’s climate is the Atlantic Ocean. Consequently, Ireland does not suffer from the extremes of temperature experienced by many other countries at similar latitude. The warm North Atlantic Drift has a marked influence on sea temperatures. This maritime influence is strongest near the Atlantic coasts and decreases with distance inland. The hills and mountains, many of which are near the coasts, provide shelter from strong winds and from the direct oceanic influence. Winters tend to be cool and windy, while summers, when the depression track is further north and depressions less deep, are mostly mild and less windy.

Polar Front

The polar front is a feature of the atmospheric circulation which plays an important part in determining Irish weather. It’s a zone of transition between warm, moist air (sometimes of tropical origin) moving northwards and colder, denser, drier air (usually of polar origin) which is moving southwards. The flow of air between the equator and the pole is complicated and indirect.

The air masses separated by the polar front are sometimes considerably modified on their paths from their respective source regions. In the North Atlantic the polar front can often be traced on weather maps as a continuous line over thousands of kilometres.

In winter, it usually extends north eastwards from the east coast of the United States, in summer it is less well-defined and can be difficult to locate. Disturbances on the front (waves), sometimes amplify and deepen to form the large scale depressions of the middle latitudes.

These depressions often move north eastwards across the North Atlantic and pass to the northwest of Ireland. Ahead of the depression centres, warm moist air is swept northwards while behind them colder, drier air is swept southwards. This gives the sequence of cloudy, humid weather with rain, followed by brighter, colder weather with showers so typical of the Irish climate.

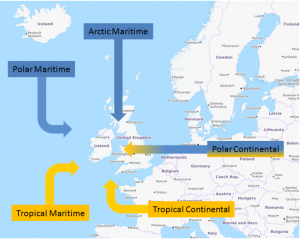

Air Masses

Ireland experiences a range of air masses with different sources and tracks, giving us our variable weather. Air masses of polar origin are most common but they usually have a long track over the Atlantic before reaching Ireland. Even southerly or south-westerly winds can bring us returning polar air, albeit highly modified by its excursion into the warm waters of the mid Atlantic.

Air masses of direct tropical or polar origin are uncommon. An examination of synoptic charts for a ten-year period showed that on average 170 fronts, which could be identified as part of the general synoptic situation, reached the south-west of Ireland each year (Rohan).

Recurrent Features of the Irish Climate

In general the Atlantic low-pressure systems are well established by December, and depressions move rapidly eastward in December and January, bringing strong winds with appreciable frontal rainfall to Ireland. Occasionally the cold anticyclone over Europe extends its influence westwards to Ireland, giving dry cold periods lasting several days.

This image details the simulated tracks of storms with a mean sea level pressure value of less than 940 hPa for the period 1981-2000, with a lifetime of at least 12 hours. These results were obtained using an ensemble of regional climate models with a resolution of 18-km. This image is re-produced from the published paper; Ensemble of regional climate model projections for Ireland, Paul Nolan, ICHEC. Future simulations predict that the tracks of these intense storms are expected to extend further south in the period of 2041 -2060, than those in the reference period of 1981-2000.

Nolan (2008) Ensemble of regional climate model projects for Ireland. EPA. Report No. 159

Between February and June, the influence of continental and Greenland anticyclones make these the months of least rainfall. The sea near Ireland is at its coldest in February and March and consequently the rise of mean air temperature is slow in spring. However, on clear days with light winds, afternoon temperatures can reach summer values even in March. In such situations the nights are cold. Air frost is not infrequent at inland locations, even in May. Continental anticyclones blocking Atlantic depressions are usually responsible for dry periods in late spring.

Towards late June or early July the rise in pressure over the ocean and a corresponding fall in pressure over Europe results in the general wind flow at the surface becoming westerly, bringing air with a long ocean track over Ireland, so that cloud cover, humidity and rainfall increase. From mid-July, clear nights tend to be accompanied by heavy dew. Warm air masses of high humidity and daytime heating sufficient to cause thunderstorms are a feature of mid to late summer weather.

With the advance of August there are occasional incursions into the Atlantic of cold northerly air masses and these produce active depressions in late August and September. In September the humid air is exposed to increasing periods of cooling by night and fog is frequent around dawn in low-lying districts.

In October and November westerly winds from the Atlantic pass over relatively warm seas, and frontal rain and post-cold frontal showers tend to be moderate to heavy. The development of anticyclones extending over Ireland in these months can produce very pleasant weather by day. However, fog in these situations is slow to clear in the morning, particularly in November when solar radiation income is low.

From late summer through Autumn there is a risk of former tropical depressions mixing in with the North Atlantic weather pattern depressions to produce severe storms. These are quite rare but are very significant weather events.

The broad sequence described above does not recur regularly each year. In an oceanic climate at the latitude of Ireland, variability of weather in some of the features referred to above may be completely missing over several months in an individual year.

Meteorological Seasons

The change from winter to spring or from summer to autumn is gradual and the general trend is subject to reversals which may last for a week or more. For climatological and meteorological purposes, on the basis of air temperature, seasons are regarded as three – month periods as follows: December to February – winter, March to May – spring, June to August – summer and September to November – autumn. This is a common grouping in the meteorological practice of many countries in the middle and northern latitudes.

Snowfall in Ireland

January and February are the months in which snow is most frequent but it’s not uncommon to have snow in any of the months November to April. Snow has been reported in May and September. On some of these occasions the falls have been considerable but the snow melted quickly. Generally snowfall in Ireland lasts on the ground for only a day or two. Some of the more notable snowfalls in recent times had snow lying on the ground lasting from 10 to 12 days.

Many Irish winters are free from major snowstorms, but because of its infrequent and irregular occurrence, snow in large quantities causes serious disruption. It can completely disrupt traffic, close airports and seriously damage overhead power lines and communication lines.

The number of days with snow cover tends to increase northwards through the Midlands corresponding to the decrease in winter air temperatures. During the winter, sea temperatures are warmer than land which can often lead to rain around the coasts but snow a few miles inland.

Rain showers may fall as snow on higher ground as temperature generally decreases with altitude. The number of days with snow cover is quite variable from year to year (find out more in our Snowfall in Ireland report from November 2012).

Met Éireann headquarters with a blanket of snow (2010)