Climate change refers to long-term changes in the Earth’s climate system, including shifts in weather patterns and average temperatures. Interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, ice sheets, land masses and vegetation create the climate system. While natural variability, such as El Niño and La Niña events or long-term cycles in the Earth’s orbit can influence the climate, the rapid warming observed since the mid-nineteenth century cannot be explained by natural factors alone.

Sophisticated Earth System Models, which simulate the interactions of natural and human influences on the climate, show that the observed rise in global temperatures is primarily driven by human activities, particularly the emission of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). These emissions trap heat in the atmosphere, intensifying global warming and triggering widespread and unprecedented changes in the climate system.

The Carbon Cycle is a vital component of the Earth system, playing a key role in regulating the planet’s climate and supporting life. This video illustrates the complex processes involved in the movement of carbon between the atmosphere, oceans, land, and living organisms, and highlights its importance in understanding climate change.

Climate change driven by human activities has caused global surface temperatures to rise by 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels over the period 2011-2020 [1]. 2024 was the warmest year on record globally, and the first year where global temperatures were 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels [2].

This warming is already leading to environmental changes, including more frequent and intense heatwaves, heavy rainfall, droughts, and rising sea levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warn that without immediate and substantial reductions in emissions, global warming is likely to surpass 1.5°C in the near future, exacerbating these impacts.

To limit warming and reduce risks, urgent and sustained action is needed across all sectors to achieve net-zero CO₂ emissions by mid-century. Additionally, enhanced adaptation efforts are critical to managing the current and future impacts of climate change, with a focus on equity and supporting vulnerable populations. Every fraction of a degree of warming avoided can significantly lessen the severity of these changes, underscoring the need for coordinated global action.

Met Éireann’s work on Climate Change

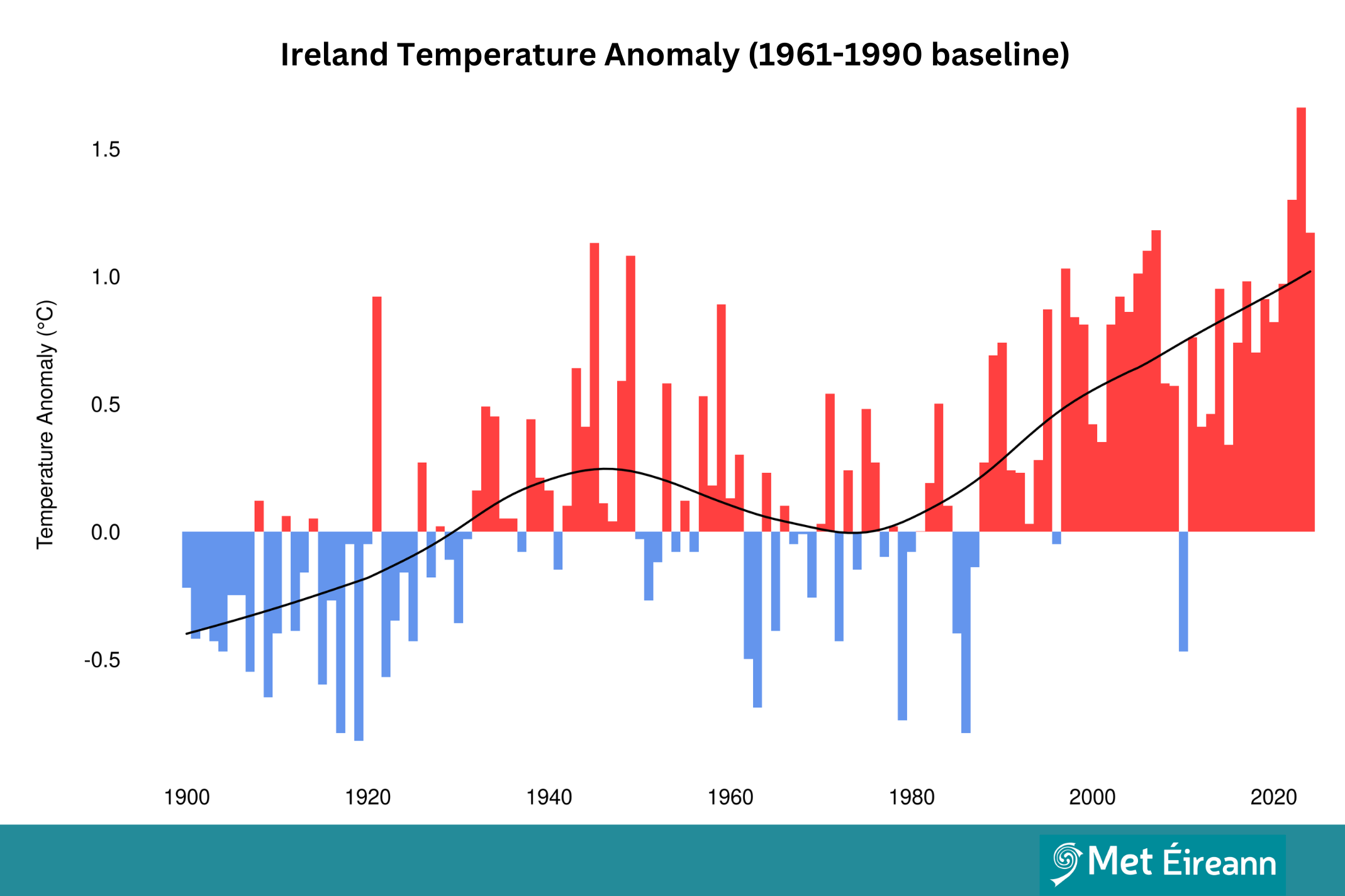

Met Éireann have a wealth of climate data from our Observation Network which allow us to undertake analysis of past climate. We use this data to calculate 30-year climate averages, which show that Ireland has become 0.7°C warmer and 7% wetter when comparing the 1961-1990 and 1991-2020 periods. The graph below shows temperature anomalies on the island of Ireland from 1900 to present, compared to the 1961-1990 period. We also produce future climate change projections for Ireland via the TRANSLATE Project.

Ireland’s temperature anomaly against the baseline period 1961-1990. The black line is a LOESS trendline, which uses a 42-year window to smooth out patterns in the data over time.

Ireland’s temperature anomaly against the baseline period 1961-1990. The black line is a LOESS trendline, which uses a 42-year window to smooth out patterns in the data over time.

Met Éireann conducts climate modelling research, both at a regional and global scale, in support of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Research is ongoing into the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, for the latest state of the science, see our dedicated AMOC webpage.

What are Greenhouse gases?

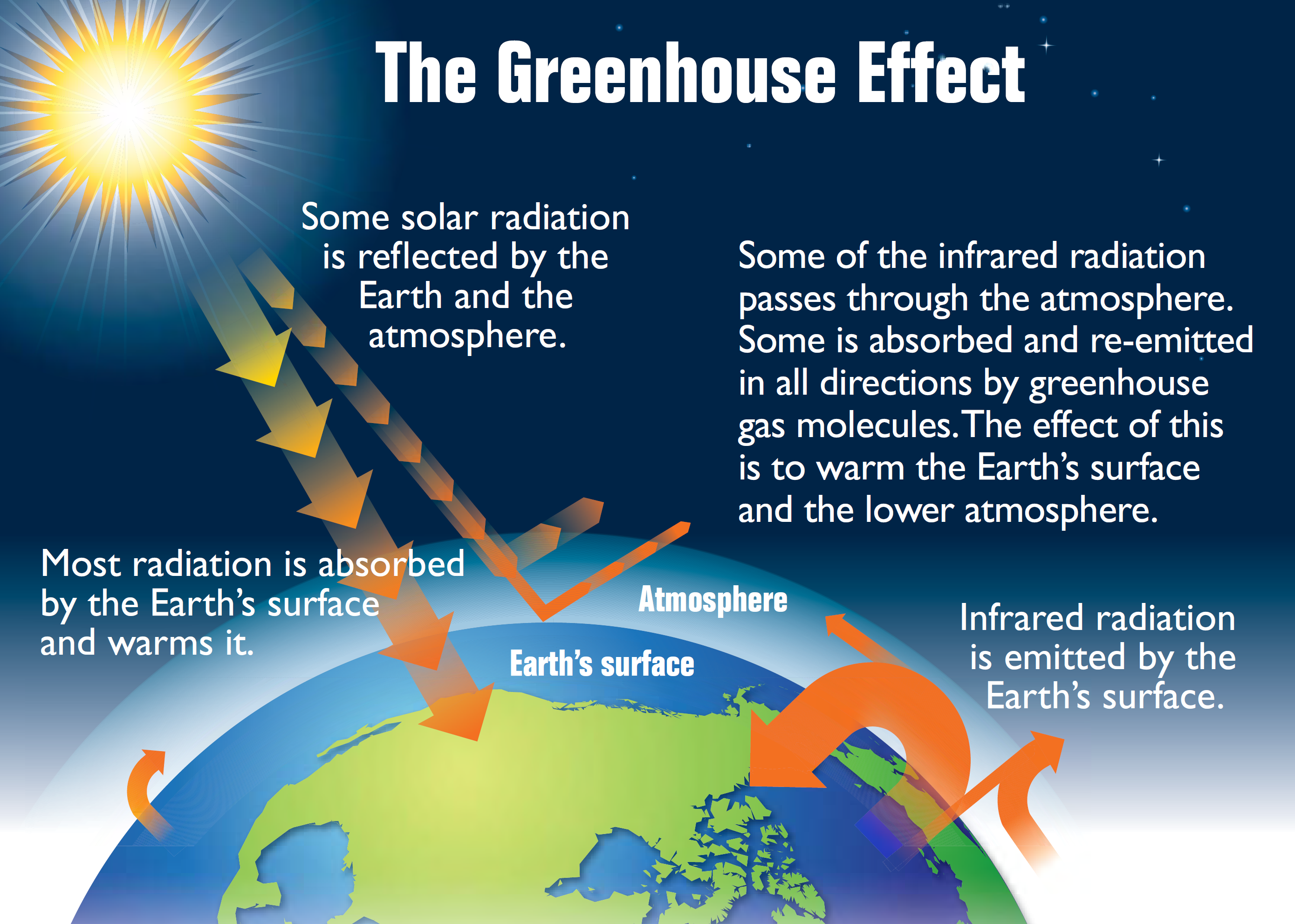

Greenhouse gases absorb and re-emit the Earth’s outgoing infrared radiation, trapping heat within the atmosphere. This natural process, known as the greenhouse effect, is crucial for maintaining the Earth’s climate. Without greenhouse gases, Earth’s average temperature would be -18°C. However, since the mid-19th century, human activities such as burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes have significantly increased greenhouse gas concentrations, leading to an enhanced greenhouse effect and climate change.

For the Earth’s climate to remain balanced, the energy it absorbs from the Sun (solar radiation) should equal the energy it radiates back into space. Most of the outgoing energy is in the form of infrared radiation. Greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), water vapor (H₂O), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and ozone (O₃), absorb this infrared radiation and re-emit it in all directions, including back to the Earth’s surface. As concentrations of these gases increase, more infrared radiation is absorbed and re-emitted, reducing the heat lost to space. This results in a net energy imbalance, causing the planet to warm.

Climate Models

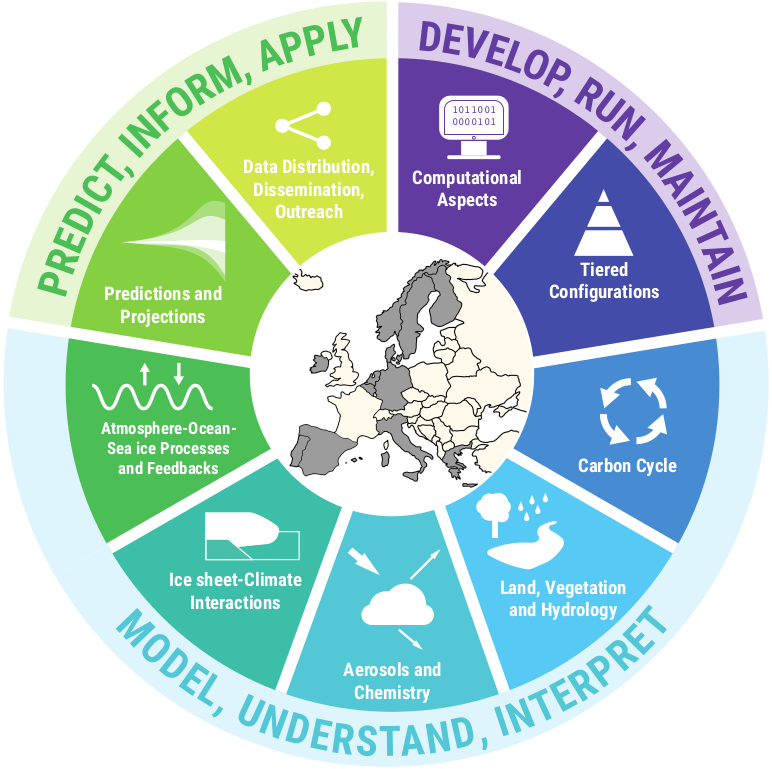

Climate models, also known as Earth System Models, are powerful tools for understanding and predicting climate behaviour over time scales ranging from seasons to centuries. These models use complex mathematical equations to simulate the interactions within the Earth’s climate system, including processes involving the atmosphere, oceans, land surfaces, and sea ice. Modern climate models integrate advanced physics, chemistry, and biology to capture feedback mechanisms such as those related to carbon cycles and vegetation. They require vast computational resources and are run on cutting-edge supercomputers.

While climate models have improved significantly, they are not without limitations. Sources of uncertainty include natural variability in the climate system, the inherent simplifications in model formulations, and unknown future emissions of greenhouse gases and pollutants. To address these uncertainties, scientists run ensembles of simulations, using multiple models and a range of scenarios for future atmospheric conditions. This ensemble approach provides a more robust understanding of possible climate outcomes and helps guide decision-making in a changing world.

The EC-Earth European consortium was set up to develop a new improved fully coupled atmosphere-ocean-land-biosphere global climate model. Met Éireann and the Irish Centre for High End Computing (ICHEC) form the EC-Earth consortium for Ireland.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established in 1988 by the United Nations, assesses the latest scientific research on climate change and publishes comprehensive reports every 5–7 years. The Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), released in stages between 2021 and 2023, represents the most comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis of climate science.

AR6 introduced the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) framework, which integrates socioeconomic scenarios with greenhouse gas concentration pathways to explore possible climate futures. These scenarios, ranging from low-emissions pathways (e.g., SSP1-1.9) to high-emissions pathways (e.g., SSP5-8.5), provide insights into the potential impacts of different policy and societal choices.

- Human influence on the climate system is unequivocal, with global surface temperature reaching approximately 1.1°C above 1850–1900 levels by 2011–2020.

- Global warming is occurring at an unprecedented rate, and many observed changes, such as rising sea levels and shrinking glaciers, are irreversible over centuries to millennia.

- Limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C requires immediate, deep, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, with global emissions needing to peak before 2025 to achieve these targets.

- Without significant mitigation efforts, global temperatures could exceed 2°C by 2100 under high-emission scenarios, leading to widespread and severe impacts on ecosystems, human systems, and economies.

- Atmospheric CO₂ concentrations are higher than at any time in at least 2 million years, and concentrations of CH₄ and N₂O were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years.

How will climate change affect Ireland?

The TRANSLATE project is a Met Éireann lead initiative to standardise future climate projections for Ireland and develop climate services that meet the climate information needs of decision makers. It is a collaborative effort led by climate researchers from University of Galway – Irish Centre for High End Computing (ICHEC), and University College Cork – SFI Research Centre for Energy, Climate and Marine (MaREI), supported by Met Éireann climatologists.

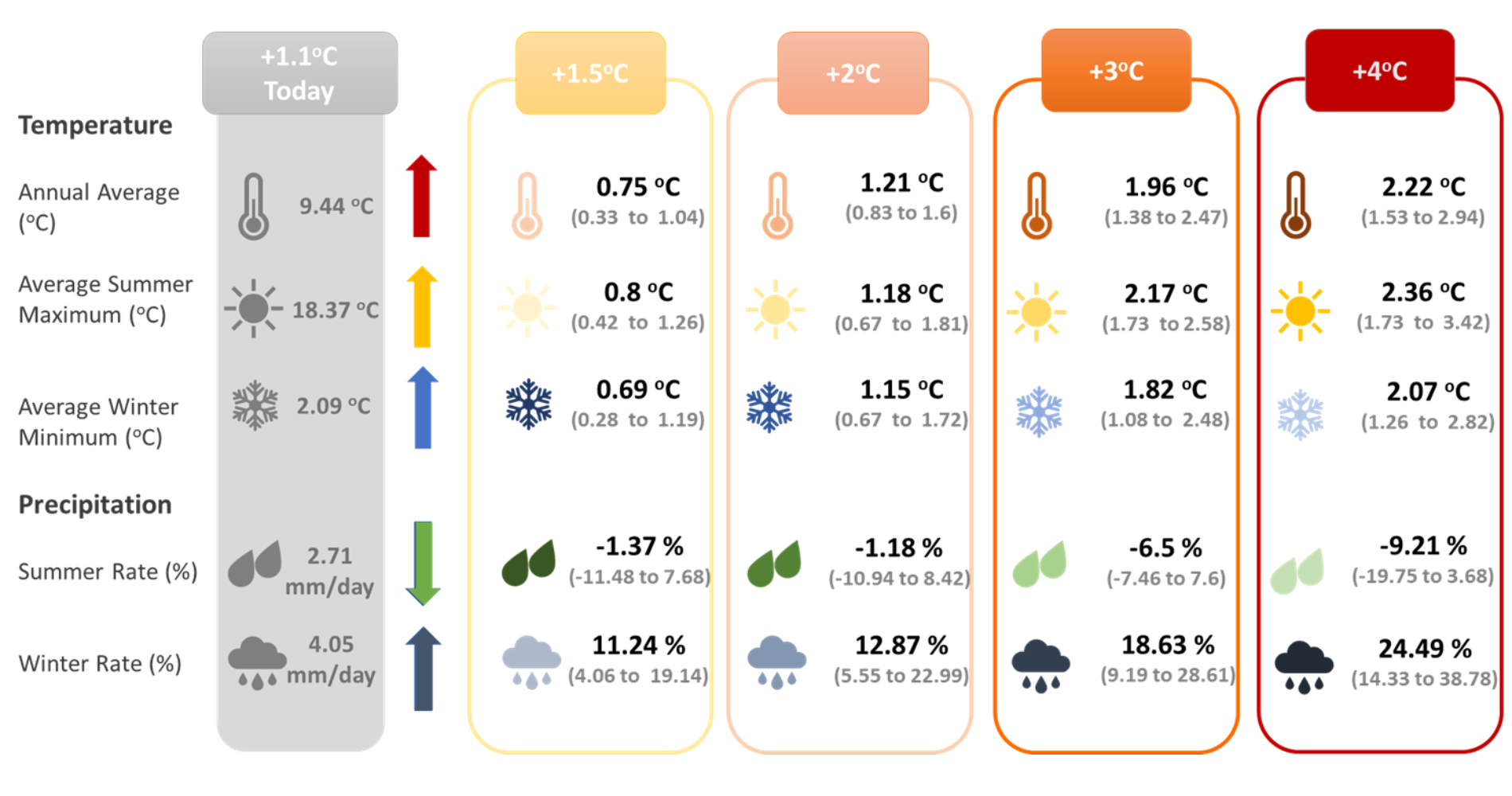

The TRANSLATE projections are provided for a range of future scenarios (both Representative Concentrations Pathways and Global Warming Levels), as Ireland’s future climate will depend on global greenhouse gas emissions reductions. TRANSLATE provides a range of future scenarios which indicate that Ireland will continue to warm, and rainfall patterns will change. The severity of the change will depend on the degree of future warming.

- Temperature Changes:

- Summer: Average maximum summer temperatures could rise by more than 2°C, leading to hotter summers and an increased frequency of heatwaves.

- Winter: Average minimum winter temperatures could also increase by more than 2°C. This will have impacts on agricultural growing seasons as well as the prevalence of pests and diseases.

- Precipitation Changes:

- Summer: Rainfall may decrease by approximately 9%, potentially causing water shortages and affecting agriculture.

- Winter: Rainfall could increase by up to 24%, elevating the risk of flooding in various regions.

The graphic below shows changes to summer and winter temperatures and precipitation at different levels of global warming.

The table above demonstrates how key climate variables for Ireland could change under different global warming thresholds. the world has currently warmed to 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels and so the grey box represents Ireland’s current climate. The average change across all models are the central figures in bold in each column. The range (or spread) across all models is presented in grey in brackets beneath it. The first value – the lower limit in the range is the 10th percentile (90% chance of being greater than this value) while the second value – the upper limit in the range is the 90th percentile (90% chance of being less than this value) of the ensemble.

These projections underscore the necessity for comprehensive climate adaptation and mitigation strategies to address the multifaceted challenges posed by climate change in Ireland.

For more information on future climate change in Ireland, including county-level projections, visit the TRANSLATE webpage.

Climate Services in Met Éireann

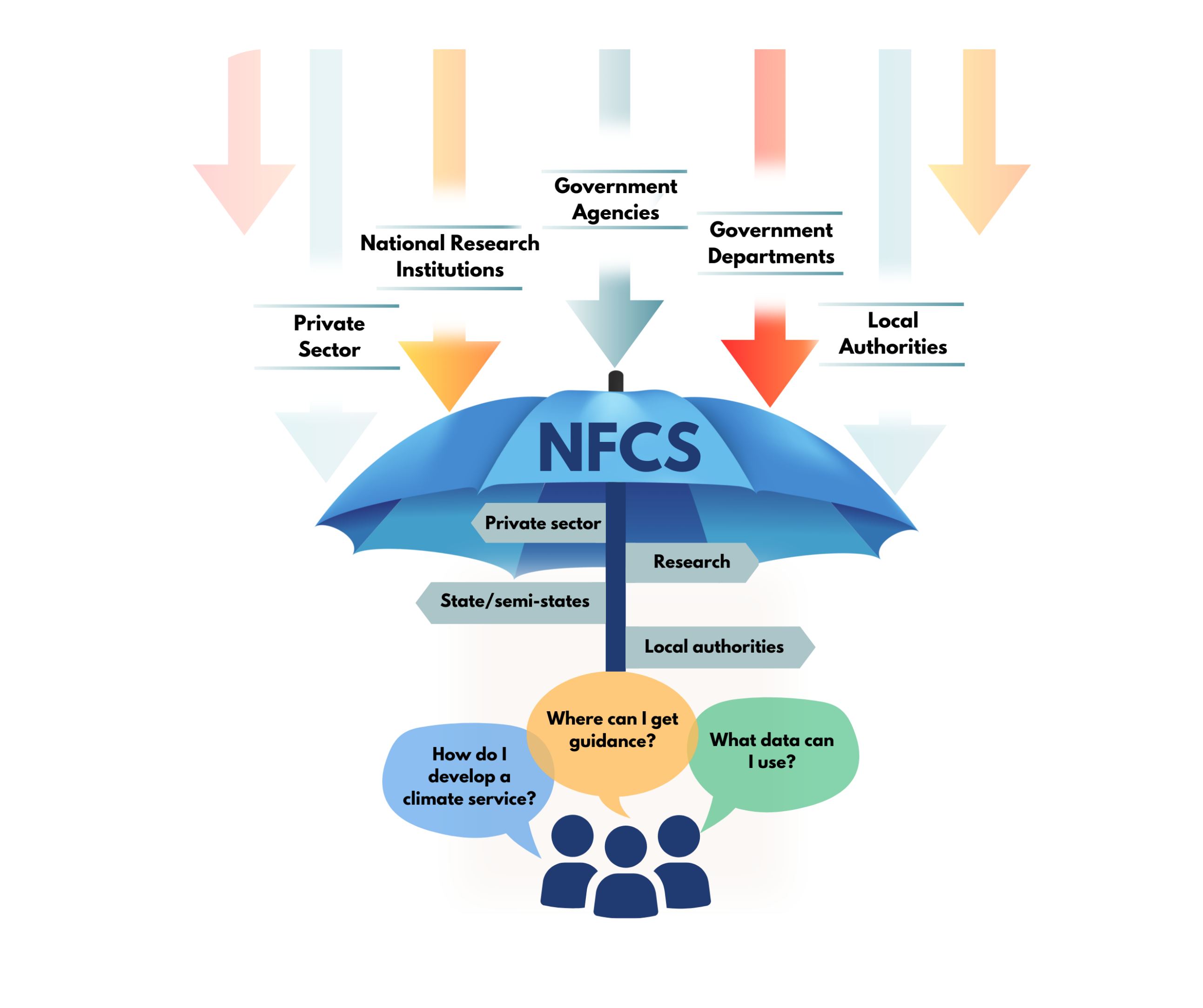

In addition to providing historical climate analysis and future climate projections, Met Éireann also coordinate the National Framework for Climate Services (NFCS). A “Climate Service” is the provision of climate information to assist in climate-smart decision-making.

The NFCS links climate services and climate information activity within Ireland, to promote and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and information and provide robust information and emerging science to support a climate resilient Ireland. The NFCS serves to promote existing information (for example the TRANSLATE project) as well as signposting relevant climate information for sectors and users.

The NFCS supports Ireland’s Climate Action Plan , the National Climate Change Risk Assessment, and Sectoral Adaptation Plans.

More information on the NFCS is available on the dedicated webpage.

More information on the NFCS is available on the dedicated webpage.

Sea Level Rise

Global mean sea level has risen about 21–24 cm since 1880. The rising water level is mostly due to a combination of melt water from glaciers and ice sheets and thermal expansion of seawater as it warms. In 2023, global mean sea level was 101.4 mm above 1993 levels, making it the highest annual average in the satellite record (1993-present).

The global mean water level in the ocean rose by 3.6 mm per year from 2006–2015, which was 2.5 times the average rate of 1.4 mm per year throughout most of the twentieth century. By the end of the century, global mean sea level is likely to rise at least 0.3 m above 2000 levels, even if greenhouse gas emissions follow a relatively low pathway in coming decades [3].

You can use the tool below to explore the sea level projections outlined by the IPCC [1].

All major cities in Ireland are in coastal locations subject to tides, any significant rise in sea levels will have major economic, social and environmental impacts. Rising sea levels around Ireland would result in increased coastal erosion, flooding and damage to property and infrastructure.

NASA Sea Level Projection Tool

Wind Energy Projections

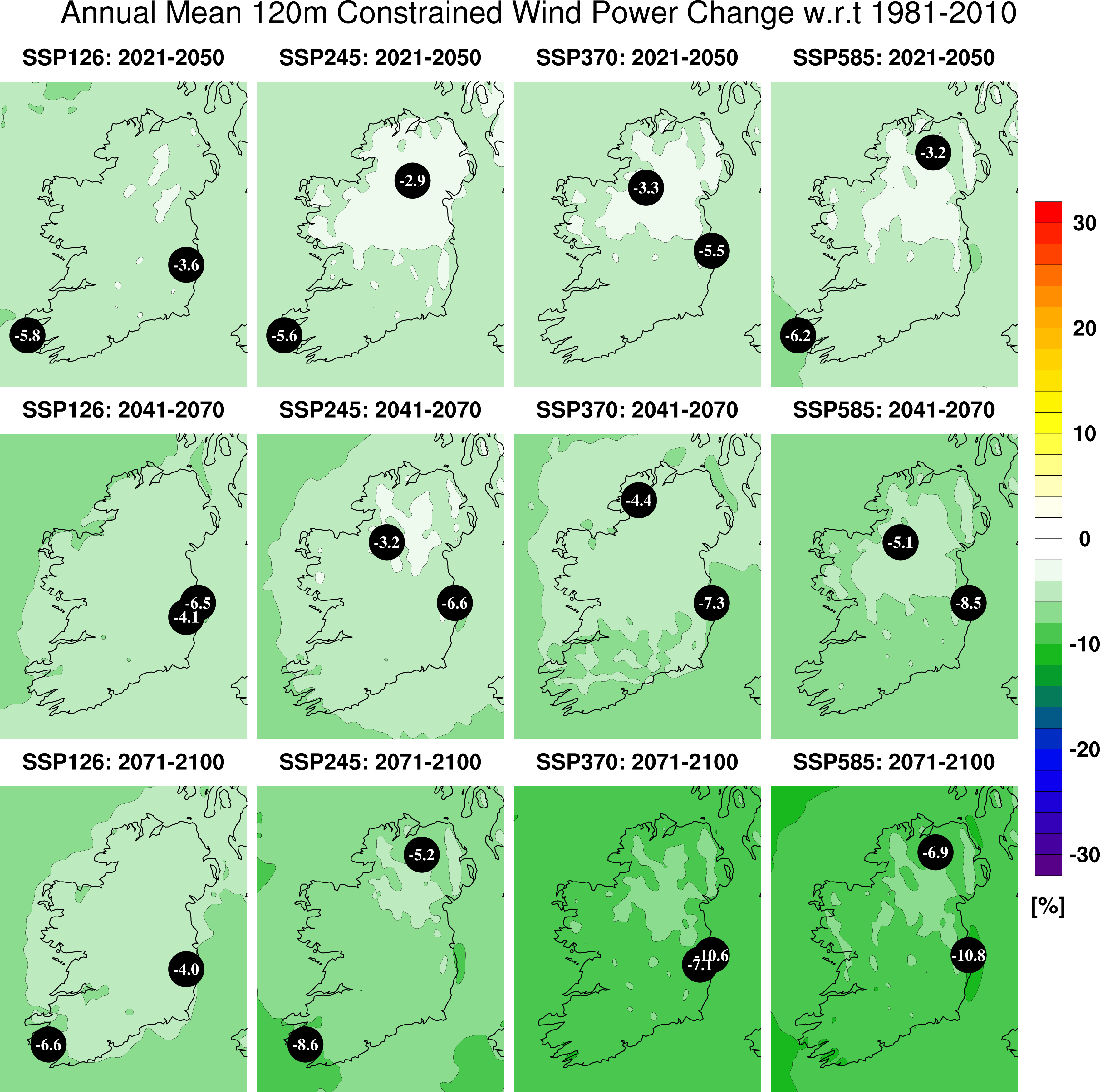

The latest downscaled climate model projections for Ireland using CMIP6 data [4] indicate that the Ireland’s annual constrained wind power is projected to decrease by 3.6–5.8% for a low emissions scenario in the period (2021–2050) and by 6.9–10.8% for a high emissions scenario by the late 21st century (2071–2100). The figure below illustrates the projected changes across the 21st century for a range of future scenarios.

Changes in nature

Climate change threatens native nature and biodiversity in Ireland and can lead to the incursion of new pests and diseases, and invasive species. Nature can also be utilized to protect us against climate change, and nature-based solutions including ecosystem restoration can be used to sequester greenhouse gases while also facilitating adaptation.

The EU’s nature restoration law (adopted in 2024) aims to restore ecosystems, habitats and species across the EU’s land and sea areas in order to enable the long-term and sustained recovery of biodiverse and resilient nature, while also contributing to achieving the EU’s climate mitigation and climate adaptation objectives. [5]

Ireland’s Nature Restoration Plan, which emerged from the EU’s nature restoration law, will facilitate the implementation of biodiversity preservation and nature-based solutions. [6]

Mitigation and Adaptation

Mitigation is action taken to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions, or to enhance carbon sinks (a natural or artificial system that absorbs and stores more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than it releases). Adaptation is action taken that helps reduce vulnerability and exposure to current or expected climate change. Ireland’s Climate Action Plan [7] outlines carbon budgets and sectoral emissions ceilings and sets a course for Ireland to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero no later than 2050.

Ireland’s National Adaptation Framework (NAF) [8] sets out the national strategy to reduce the vulnerability of the country to the negative effects of climate change and to avail of potential positive impacts. The NAF outlines a whole of government and society approach to climate adaptation in Ireland.

The NFCS supports the NAF by enabling sectors to develop and implement sectoral adaptation plans (SAPs). See here for more information on how the NFCS can support SAPs.

Further Reading, Links and References

- IPCC, 2023: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-34, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. (2025, January 10). Global Climate Highlights 2024. European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. Retrieved from https://climate.copernicus.eu/global-climate-highlights-2024

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (n.d.). Climate change: Global sea level. Climate.gov. Retrieved from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

- Nolan, P. (2024). Updated high-resolution climate projections for Ireland (EPA Research Report No. 472). Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.ie/publications/research/climate-change/research-472-updated-high-resolution-climate-projections-for-ireland.php

- EU Nature Restoration Law. Environment. from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/nature-restoration-law_en

- National Parks & Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Minister Noonan announces next step in the development of Ireland’s Nature Restoration Plan. Retrieved January 13, 2025, from https://www.npws.ie/news/minister-noonan-announces-next-step-development-ireland%E2%80%99s-nature-restoration-plan

- Government of Ireland. (2024). Climate Action Plan 2024: Accelerating decarbonisation. Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications. Retrieved from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/79659-climate-action-plan-2024/

- Government of Ireland. (2024). National Adaptation Framework: Planning for a climate resilient Ireland. Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment. Retrieved from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/fbe331-national-adaptation-framework/